Article 17 Of Indian Constitution: “Untouchability” In Quotation Marks

Atul Kumar Dubey

3 Oct 2025 6:00 PM IST

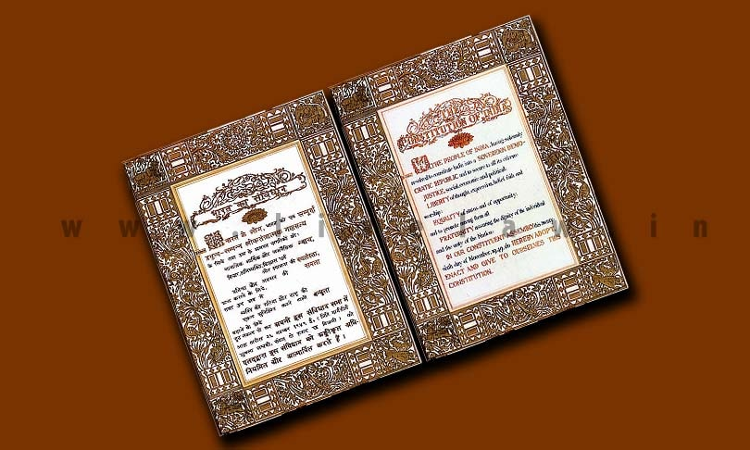

The Constitution of India has been designed with its own specificity where the founding members choose to write down the social, political and economic transformation. Various constitutions around the globe may have inspired the making of the Indian Constitution, however, the choice of words, style and specificity in drafting has been unique to India. One such instance is the inclusion of a provision relating to untouchability. Article 17 of the Constitution states:

“Untouchability” is abolished and its practice in any form is forbidden. The enforcement of any disability arising out of “Untouchability” shall be an offence punishable in accordance with law.

Noticeably, the word “Untouchability” appears within quotation marks. The use of inverted commas in the provision is not a small typographical choice but a deliberate choice, having larger implications on how Article 17 is read and applied.

Constituent Assembly Deliberations:

The drafters of the Constitution acknowledged the age-old social practice of untouchability as reflected in the draft articles prepared by Shri K.M. Munshi and Dr. B.R. Ambedkar”[2] in the Sub-Committee on Fundamental Rights. The Draft Article III Clause 4(a) prepared by Shri Munshi read as:

“Untouchability is abolished and the practice thereof is punishable by the law of the Union.”[3]

The Sub-Committee, in its report, accepted the draft prepared by Shri Munshi as Draft Clause 6 as:

““Untouchability” is abolished and the practice thereof shall be an offence”.[4]

It is significant to note that for the first time, the Sub-Committee used the quotation marks for the phrase untouchability. Shri B.N. Rao, on the Draft Report on April 4, 1947, noted that the meaning of the practice of untouchability will have to be defined in the law meant to implement this provision.[5] Later, the Sub-Committee decided to add the phrase “in any form” after “untouchability”. When the Clause was deliberated in the Advisory Committee, members like Shri Jagjivan Ram, Shri C. Rajagopalachari and Shri K.M. Panikkar wanted the clause to spell out clearly the abolition of untouchability within a community or between various communities.[6] Thus, Clause 6 in the report of the Advisory Committee appeared as:

““Untouchability” in any form is abolished and the imposition of any disability on that account shall be an offence.”[7]

When the clause came up for consideration before the Constituent Assembly, Shri P. Kunhiraman proposed an amendment to add “punishable by law” after the word “offence”. The Drafting Committee again considered the provision on October 30-31, 1947 and the clause appeared as Draft Article 11 in the following form: ““Untouchability” is abolished and its practice in any form is forbidden. The enforcement of any disability arising out of “Untouchability” shall be an offence punishable in accordance with law.” When the Draft Article 11 came up for debate, Shri Naziruddin Ahmad proposed an amendment to substitute the clause as: “No one shall on account of his religion or caste be treated or regarded as an 'untouchable'; and its observance in any form may be made punishable by law”.[8] He argued that the Draft Article is vague with no legal meaning and is prone to misunderstanding. He noted that:

“The word 'untouchable' can be applied to so many variety of things that we cannot leave it at that. It may be that a man suffering from an epidemic or contagious disease is an untouchable; then certain kinds of food are untouchable to Hindus and Muslims. According to certain ideas women of other families are untouchables. Then according to Pandit Thakurdas Bhargava, a wife below 15 would be untouchable to her loving husband on the ground that it would be 'marital misbehaviour'. I beg to submit, Sir, that the word 'untouchable' is rather loose. That is why I have attempted to give it a better shape; that no one on account of his religion or caste be regarded as untouchable. Untouchability on the ground of religion or caste is what is prohibited.”[9]

Shri V.I. Muniswamy Pillai, in his support of the Draft Article, argued that the 'untouchables' will find solace when the Constitution comes into effect.[10] Another member, Shri Santanu Kumar Das, extended support, stating that the Draft Article was intended to abolish the social inequity, the social stigma and the social disabilities in our society.[11] However, Shri K.T. Shah raised the concern that the term is not defined and raised concern relating to the scope as to whether the term includes certain religious practices relating to women, as:

“We all know that at certain periods women are regarded as untouchables. Is that supposed to be, will it be regarded as an offence under this article? ……. Again there are many ceremonies in connection with funerals and obsequies which make those who have taken part in them untouchables for a while. I do not wish to inflict a lecture upon this House on anthropological or connected matters; but I would like it to be brought to the notice that the lack of any definition of the term 'untouchability' makes it open for busy bodies and lawyers to make capital out of a clause like this, which I am sure was not the intention of the Drafting Committee to make. One more example I will give, Sir, which is of a hygienic, or rather sanitary, character, that seems to be completely overlooked by the draftsman. What about those diseases, and people who suffer from, which are communicable, and so necessarily to be excluded and made untouchables while they suffer?”[12]

The amendment proposed by Shri Naziruddin was negated, and Dr. Ambedkar did not reply to the queries raised by Shri Shah. Finally, Draft Article 11 was adopted and included as Article 17. The Constituent Assembly deliberately did not define the term with the intention of providing legislative flexibility. Significantly, in the Assembly, there was no discussion on the use of quotation marks for the term.

Quotation Marks: Deliberate or Accidental

Against this backdrop, the placement of “Untouchability” in quotation marks must be analysed. The use of such a constitutional design was meant to be an open-textured and anti-exclusionary guarantee of social equality. Enclosing “untouchability” in quotation marks indicates that the word must be understood in its social and historical context. It was the clear intention of the framers, as discussed in the Assembly, to avoid a literal or narrow reading. Put simply, the quotation marks transform the word into a conceptual phrase, signifying that the practices known as “untouchability” are rooted in social disabilities. Further, the addition of the phrase “in any form” after the word “Untouchability”, ensured that the remedial measure includes all manifestations of the practice. The drafting choice made by the framers seeking to abolish both the practice and the stigma of untouchability.

The significance of placing “untouchability” under inverted commas was recognised by the Mysore High Court in Devarajiah v. B. Padmanna.[13] The High Court held that the absence of definition in the Constitution and the use of inverted commas indicate that the practices in the course of historical development are the subject matter. The High Court observed:

“There is no definition of the word 'Untouchability' in the Constitution also. It is to be noticed that word occurs only in Art. 17 and is enclosed in inverted commas. This clearly indicates that the subject-matter of that Article is not untouchability in is literal or grammatical sense but the practice as it had developed historically in this country.”[14]

It is interesting to note that Shri Munshi, during the debate on April 29, 1947, referred to the use of the inverted commas, describing them as being “put purposely within inverted commas in order to indicate that the Union legislature when it defines 'untouchability' will be able to deal with it in the sense in which it is normally understood”.[15] On similar lines, Justice DY Chandrachud (as he was then) in Indian Young Lawyers Association v. State of Kerala[16] observed that the use of a punctuation mark cannot be construed to circumscribe the constitutional width attached to the expression. The opinion also emphasised that the provision must be interpreted in its historical backdrop of subjugation, discrimination and social exclusion. In his seminal work, H.M. Seervai, too, has emphasised that untouchability in inverted commas is not interpreted in its literal and grammatical sense but practices as developed historically in India.[17]

In sum, placing the term “untouchability” in the inverted comma is a form of constitution-making device, reflecting the framers' recognition of the practice as a social phenomenon with historical roots. The unique constitutional design ensures that the term must be interpreted to include all forms of social disability and stigma flowing from the social ostracism.

Author is a Research Scholar at Rajiv Gandhi School of Intellectual Property Law, Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur. Views are personal.

2. B Shiva Rao, Framing of India's Constitution, Select Documents, Vol. 2, pg. 86; See also Draft Article II Section 1 Clause 1 read as “All persons born or naturalized within its territories are citizens of the United States of India and of the State wherein they reside. Any privilege or disability arising out of rank, birth, person, family, religion or religious usage and custom is abolished”. ↑

3. B Shiva Rao, Framing of India's Constitution, Select Documents, Vol. 2, pg. 74. ↑

4. Id. pg. 138. ↑

5. Id. pg. 148. ↑

6. B Shiva Rao, Framing of India's Constitution: A Study, pg. 202, 203. ↑

7. B Shiva Rao, Framing of India's Constitution, Select Documents, Vol. 2, pg. 297. ↑

8. Constituent Assembly Debates, Vol. VII, Nov 29, 1948 pg. 665, available at https://eparlib.sansad.in/bitstream/123456789/763032/1/cad_29-11-1948.pdf . ↑

9. Id. ↑

10. Id. ↑

11. Id. pg. 666. ↑

12. Id. pg. 668. ↑

13. 1957 SCC OnLine Kar 16. ↑

14. Id. para 10. ↑

15. Constituent Assembly Debates, Vol. III, April 29, 1947, pg. 413, available at https://eparlib.sansad.in/bitstream/123456789/762962/1/cad_29-04-1947.pdf ↑

16. (2016) 16 SCC 810. ↑

17. H.M. Seervai, Constitutional Law of India, Vol. 1, pg. 691. ↑